Kapampangan history properly begins in Spanish times, for the first written records about the Kapampangans deal with the resistance of Betis and Lubao - Muslim towns - against the encroaching Spaniards. Later records by Fr Gaspar de San Agustin, OSA discuss the town of Macabebe leading a coalition of Kapampangan Muslims against the Spanish. Whatever the case, the next few centuries consist of a litany of praises towards Kapampangans (including singling them out as exceptions from negative generalizations of indios), bureaucratic and administrative records, and military accomplishments. Before Spanish times, evidence becomes shakier. While the Kapampangans had their own writng, no records before Spanish times survive. All that we can rely on is indirect evidence: archaeological, linguistic, geological, genetic, even folktales.

Linguistic and genetic evidence

The Kapampangan language is part of the Central Luzon languages, which also includes the Sambal dialects and Hatang Kayi (Remontado Agta). The Central Luzon languages are one family in the wider Austronesian languages. Thus, while Sambals and Kapampangans were in perpetual conflict before Spanish pacification, the two peoples seemed to have come from a common ancestral tribe. While the Remontado Agta are an Aeta grouping, their genetics show high admixture with lowlanders, and their phenotype looks like a mix between Negritos and lowlanders, suggesting that their ancestors also came from that tribe.

Genetically, the Kapampangans are indistinguishable from Sambals. They also have similar genetics to Bolinao Sambals, Pangasinense, the Bugkalot (Ilongot) Igorot, and Tagalogs.

That last similarity, however, begs the question of how it happened. The Tagalog language is part of the Greater Central Philippine languages, a different macrofamily than the Central Luzon languages. Zorc1 also notes that the Tagalogs came from Eastern Samar, and migrated later on to Luzon. Thus, we would expect their genetics to be more similar with Cebuanos or the Hiligaynon, among other ethnic groups. We will return to that topic later on.

Archaeological and paleolinguistic evidence

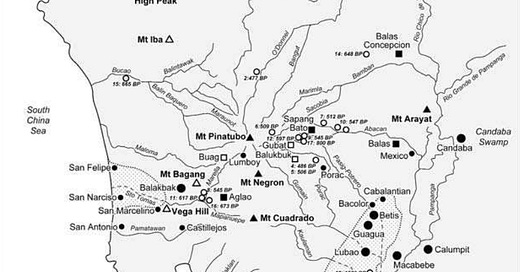

The earliest archaeological evidence in Kapampangan lands dates to 3000 BC, a stone adze (boat axe) in Candaba. Adzes also existed in Porac, and stone tools in general existed along the Eastern Zambales mountains2. Evidently, a well-developed shipbuilding people lived here. Other archaeological relics are earthenware pottery shards. However, little archaeological evidence exists after around 300 BC. This time coincided with a large eruption from Mount Pinatubo. Only wooden fragments remain as archaeological remains after this year3.

After AD 800, however, the situation changes. H Otley Beyer described Tang and Song Dynasty ceramics dating to the 9th century in Porac4. The next archaeological evidence date to around AD 1000. These consist of undecorated earthenware in Candaba. Some fragments of a small, decorated pot laced with Hematite date even older5. One may explain the gap between archaeological evidence using the Kapampangan language itself.

Linguistic evidence points to sedentary Kapampangan culture as a relatively recent development, with remnants from hunter-gatherer practices remaining with different meanings6. Indeed, that Kapampangan changed from Proto-Central Luzon with both hunter-gatherer and sedentary semantics intact points to the Kapampangans originally being hunter-gatherers, as Sambals were up to Spanish times.

As a sidenote, while some contend that the Kapampangan dayat first referred to ricefields, then to the sea (dayat a malat), it is obviously a cognate to words like the Tagalog dagat, among many other Austronesian words. One would believe that the Kapampangans, originally a nomadic group, applied the word to rice fields later. However, as the land became more important than the sea, dayat a malat became the secondary usage for the word.

After these initial finds, pottery and ceramics increasingly dot the Kapampangan lands’ landscape, showing socioeconomic development among Kapampangans. Archaeological evidence also shows that human settlement existed around an old shoreline near Manila Bay, dating to AD 13007. However, Mount Pinatubo would erupt again around AD 1500, depositing a new layer of ash and lahar around the Kapampangan lands. The Sambal and Kapampangan shorelines also expanded as the rivers deposited sediment into prehistoric bays.

Linguistics and placenames point to the eruption’s consequences. Father Diego Bergano lists the word Lubau as meaning “to pass out of a straight passage”. The town of Lubao itself rests on land that existed only after the last eruption. The town’s name must have come from sediment deposited by the Porac, Gumain, and Caulaman rivers: ding gabun na ning Lubao libau la caring ilug (the lands of Lubao passed through the rivers). Many villages also have the name Balas, meaning ‘sand’. 8 The village of Sapang Batu in Angeles means ‘creek of stones’, with rocks and sand dotting creeks and rivers located there transported by the Abacan River from Mount Pinatubo. Indeed, the Kapampangan word sibul means both ‘source’ and ‘volcano’, since many rivers in Pampanga find their source in Mount Pinatubo.

Ming Dynasty annals also point to trading outposts by an ancient bay in Zambales, along with a high mountain that could have been Mount Pinatubo. Chinese trade with Pampanga flourished for pre-eruption, rivers allowed easy access from the Zambales shoreline into Pampanga itself through Mapanuepe Lake, which was bigger before the AD 1500 eruption, and Mapanuepe river. After the eruption, the Kapampangan populace resettled in the south and east to avoid lahar flow, with Lubao, Betis, Macabebe, and Candaba being powerful communities when the Spanish came.

Folklore

A popular Kapampangan myth tells of a war between gods Apung Sinukuan (of Mount Arayat) and Apung Namalyari (of Mount Pinatubo). The latter threw rocks and boulders at the former, causing Sinukuan’s kingdom to suffer damage. Gaillard points to this myth as coming from the AD 1500 eruption. He notes that Namalyari’s other name as Apung Punsalan (chief of enmity) must have come from the eruption, for Kapampangans also referred to Mount Pinatubo by that title.

Another myth from the Aeta tells of a prehistoric lake that got buried in sediment:

Finding the lake a useless place of refuge, he climbed the Mount Pinatubo in exactly twenty-one tremendous leaps. When he had reached the top, he at once began to dig a big hole into the mountain. Big pieces of rock, mud, dust, and other things began to fall in showers all around the mountain. During all the while, he howled and howled so loudly that the earth shook under the foot of Blit, Aglao, and his hosts. The fire that escaped from his mouth became so thick and so hot that the pursuing party had to run. (Rodríguez 1918)

This myth may in fact refer to Lake Mapanuepe getting buried in the AD 1500 eruption9. Pinatubo’s very name may have come from witnesses seeing its lava dome grow before the eruption, as the legend suggests - the summit was replaced by a big hole, just as what happens when a lava dome collapses.

However, one last myth serves to tie in a few loose ends from where we started.

A Tagalog invasion?

Kapampangan tales speak of Apung Sinucuan as teaching the Kapampangans agriculture, metallurgy, logging, and war. They also describe him as a culture hero first named Sucu leading the Kapampangans in war against invaders from the south. Some sources name the invaders as the taga-ilog10, although no definitive identity exists. Oral retellings have corrupted the myth of Sinukuan into different versions. Some versions, like that recorded by Cipriano de los Reyes (1915), or by Teodulo Franco (1916), retain basic elements: enmity between Kapampangans and southerners, war between Sinukuan and a southern leader, and talks of marriage between a southerner and Sinukuan’s daughter/s. Context clues, however, allow us to piece together what may have happened to inspire the myth.

As mentioned, the Tagalog migrated from Samar around AD 800. They must have first permanently settled in Marindque, where the Tagalog dialect remains pure from foreign influence. Archaeological relics also abound there. The Tagalog migration must have continued immediately, for Tagalogs were already burying their dead in Tayabas a century after.

After landing on present-day Batangas, the Tagalog language loaned words from Kapampangan:

The replacement of PSP *hulas ‘sweat, perspiration’ by an earlier loan *pawes (Kapampangan pawas, Tagalog pawis), indicates the way Kapampangan once had penetrated in to the basic vocabulary of Tagalog. Many other loans indicate the dominance of professions by Kapampangan speakers ( karáyom ‘needle’ from

*ka-daRum for ‘tailoring’, dayami ‘rice straw’ from * daRami for ‘agriculture’, katám from *keTen for ‘carpenter’s plainer’, darak from *de(dak ‘powdered food from husk of rice’ for ‘agriculture’). Hence, Tagalogs have been enormously dependent upon the Kapampangans until they established themselves in Southern Luzon; this only makes sense for an incoming social group.Gonzalez, A. (2005). Contemporary Filipino (Tagalog) and Kapampangan: Two Philippine languages in contact. Current Issues in Philippine Linguistics and Anthropology: Parangal kay Lawrence A. Reid/Ed. by H. Liao and CR Galvez Rubino. Manila: Linguistic Society of the Philippines and SIL Philippines, 93-114.

Note that these words refer to manual labor, and involve manual work. Northern Luzon loans into Tagalog through Kapampangan, like alipin (chattel slave), daras (adze), galaw (move), and kaluban (sheath), among others, further point to the nature of the Tagalog migration.

It would seem that an initial Tagalog elite landed on Southern Luzon, then by force imposed itself on the hunter-gatherer natives. While some foreign elites, like the Rus, the Mongols, or the Ptolemies, adopt their native people’s culture, others impose their own, like the Anglo-Saxons or the Franks. This initial Tagalog elite must have used the natives for manual labor, as the loanwords show, then spread their culture to them, as genetics show. This migration would end up on the shores of Laguna de Bay, where the town of Bay (Ma-i in Chinese records11) became the prime Tagalog town in Luzon. The migration would also have pushed some natives into the Sierra Madre mountains, where they intermixed with the Aeta to become the Remontado Agta. Indeed, the Tagalogs call them Sinauna (first inhabitants), a sign that they were displaced natives.

If the initial Tagalog elite was hostile to the natives, and treated them as manual laborers, no doubt that they would have continued migrating northwards. Here we see how the Sinukuan legend may have formed:

a culture hero introduces sedentary living to the Kapampangans as preparation for an invasion;

the culture hero leads his new people in battle against the invaders; and

the culture hero becomes revered as god as time passes.

It is said that Sucu became called Sinucuan for the invaders surrendered to him (from Kapampangan sucu, meaning surrender). Either way, after this Tagalog migration, Kapampangan archaeological relics enter the record, and the Kapampangans as they are (or were) become a people in their own right. The Sambals must have been hunter gatherers who rejected adapting to new circumstances, then fled to the Zambales mountains to continue their way of life. Conjecture would have the Sambals fearful of Apung Namalyari’s wrath, if a belief set in after the 500-300 BC eruption that Namalyari punished sedentary living. Unfortunately, we may never be able to prove this.

Afterword: Early Historical Pampanga

In 1587, the town of Candaba was ruled by Dionisio Capulong. He was the son of Bunao, Lakang Dula, the Tagalog ruler of Tondo12.

In Maynila, the Tagalog natives kept to either animism or a butchered version of Islam, while the elite were devout Muslims13. Tondo, however, kept to Tagalog animism. Some contend that Tondo was the southernmost Kapampangan town, and that the Pasig River was the initial division between Kapampangan and Tagalog towns. However, evidence suggests otherwise:

Obando holds annual rites originally in commemoration for Tagalog gods: Lakampati (hermaphrodite patron of fertility, reproductive and agricultural), Dian Masalanta (Makiling), and Bathala (Hindu title for the unnamed Tagalog god, borrowed from bhattara meaning noble lord14). Obando was also named Catanghalan, or “place where the festivities are held”, in clear reference to the rites. If Tondo was the southernmost Kapampangan town, Obando (due north of Tondo) would be celebrating Kapampangan gods instead.

The town of Navotas comes from the Tagalog “nabutas”, referring to Manila Bay piercing into an inland body of water. If Kapampangans still settled here by Spanish times, then a town named “Butas” could never have led the Battle of Bangkusay Channel.

Prominent Kapampangans in Tondo, like Panday Pira or Juan Macapagal, had their own reasons to stay there: Panday Pira was hired by Lakang Dula to forge cannons against the Spanish, while Juan Macapagal was related to Tondo’s rulers, and probably had inherited land, or stayed with family.

Bunao, Lakang Dula, introduced himself as si Bunao Lakandula to the Spanish. In other words, he introduced himself in Tagalog, not Kapampangan. The title Laka is also a Tagalog one15, a borrowing from Javanese raka. The title would not be loaned into Kapampangan until the 20th century (Bergano’s dictionary has no mention of the word). A Kapampangan ruler over a Kapampangan populace would have used a Kapampangan title, and would have spoken in Kapampangan.

While Lakang Dula agreed to help the Spanish win over the Kapampangans, Muslim Kapampangans refused to submit even after Maynila’s fall. Fr Gaspar de San Agustin writes that Bambalito of Macabebe first led a coalition of Kapampangan Muslims against Spain in Bangkusay Channel, only to be defeated. Earlier sources, however, note that it was Tagalog towns along Manila Bay like Navotas that fought in Bangkusay, with no mention for whether they were Muslim or not. Betis and Lubao kept up resistance for longer, till they also fell.

Maynila’s fall sent shockwaves to Brunei, whose Sultan refused to surrender to Spain. The Spanish besieged Brunei in 1579, and sacked it, only to retreat after running low on supplies and catching disease. In retaliation, the Bruneian aristocracy in Maynila hatched a conspiracy to overthrow Spanish rule and restore Bruneian suzerainty. Lakang Dula’s sons, including Dionisio Capulong, joined them.

In 1585, a Kapampangan nobleman, Don Juan de Manila, engaged in a squabble with the Spanish administration over tribute and tax collection. He also wanted revenge over the Spanish favoring his subjects and serfs over him, a nobleman. He and a friend, Don Nicolas Mananguete, promptly collected fifty retinue arquebusiers and warriors each to take Candaba by force. One of Don Juan’s relatives, probably the chief of Candaba, tried to persuade him to stop, only to be killed and robbed. They would go on to kill and rob boatmen and passengers going through the Pampanga river. A Master of Camp was deployed to stop them, only to be defeated. However, Mananguete surrendered in exchange for a pardon and for his Confessor to go with him. Juan de Manila, on the other hand, kept stubborn and continued his fight. The Master of Camp used cunning tactics to defeat his forces in a siege, killing them to the last man when they tried breaking out:

The maestre ordered a siege with other indios of the land. The maestre got a dozen of them in the guise of travellers. They went to the hideout of Juan de Manila who went out to meet them with his men and were shot as they fled. They were all killed without exception.

With the chief of Candaba dead, Capulong himself became chief by 1588. It is unknown how a Tagalog nobleman could have become chief of a Kapampangan town, but it is likely that Capulong’s mother was a Kapampangan native of Candaba. By Kapampangan tribal law, any capable man could challenge a town’s leadership to become chieftain himself16. Either way, Capulong must have joined the conspiracy for family ties alone. The other conspirators tried convincing the Kapampangans to join them, promising that they could keep their serfs and peons, which the Spanish had tried to ban in Pampanga. Don Juan’s insurrection itself came from disputes over serfdom. The Kapampangans refused, however:

Moreover it appears that about the same time, when certain Indian chiefs of Panpanga came to Manila on business connected with their province, on passing through the village of Tondo, Don Agustin Panga summoned them; and he, together with Don Agustin de Legaspi, Sagat Malagat, and Amanicalao, talked with them, and inquired after the business that took them to Manila. The chiefs answered that they came to entreat the governor to command the cessation of the lawsuits concerning slaves in Panpanga, until they could gather in the harvest. Don Martin said that this was very good, and that they also wished to make the same entreaty and to bring their slaves to court; but that to attain this it would be best to assemble and choose a leader from among them, whom they should swear to obey in everything as a king, in order that none should act alone. The chiefs of Panpanga said that they had [no] war with the Spaniards, to cause them to plot against the latter, and that they had a good king. Thus they did not consent to what was asked from them by the aforesaid chiefs, and proceeded to Manila in order to transact their business. In Manila they were again invited to go to Tondo, to take food with the plotters; but the Panpanga chiefs refused.

The conspiracy failed. Larkin also notes that serfdom and peonage remained in Pampanga till the mid-17th century, vindicating Kapampangan loyalty to Spain. Capulong was one of those tried. Unlike the other conspirators, who were executed or exiled to Mexico, Capulong himself was merely exiled from Intramuros:

Dionisio Capolo, chief of Candava, was sentenced to prescribed exile from this jurisdiction for eight years, and was condemned to pay fifteen taels of orejeras gold, 93 half of which was to be set aside for the treasury of his Majesty, and half for judicial expenses. He and the fiscal appealed to the royal Audiencia, which, after having examined the report of the trial, remitted it to the captain-general, in order that justice might be done–save that the whole penalty was to consist of four years of prescribed exile, and the payment of twelve taels of orejeras gold. The sentence was executed.

Governor-General de Vera would pardon him anyhow, and Capulong could have just stayed in his home in Candaba during his exile. Capulong would go on to help the Spanish conquest of the north, starting centuries of a Kapampangan-Spanish alliance. His son, Juan Gonzalo Capulong, went to begin the Macapagal (“tiring”) family17.

The last mention of Dionisio Capulong is in a document dated 7 October 1620, mending a land squabble between him and Agustin Huyca, whom he had sold land too last January. By this time, Capulong had settled in Tondo, while the Kapampangans continued growing as a people of their own.

Summary

~500-300 BC: Early human settlement of Kapampangan lands disrupted by Mount Pinatubo eruption; nomadic groups settle the Central Luzon plain for the next millennium.

~AD 800: Tagalog migration to Marinduque and Luzon. Remontado Agta flee to the mountains, then intermix with Aeta. Possible inspiration for Sinukuan culture hero happens when proto-Kapampangan hunter gatherers stop the migration, then become a sedentary people.

~AD 800-1200: early Kapampangan development. Sedentary living becomes norm. Candaba and Porac become first among Kapampangan towns.

AD 1200-1500: Kapampangan economic flourishing, with trade across South China Sea.

~AD 1500: Mount Pinatubo erupts, expanding the shoreline and disrupting Kapampangan life. Afterwards, Muslims settle and convert many Kapampangans, forming the towns of Betis, Lubao, and Macabebe.

AD 1570: Spanish arrive in Luzon.

AD 1571: Battle of Bangkusay Channel.

AD 1572: Spanish conquest of Betis and Lubao.

AD 1579: Spanish expedition to Brunei fails.

AD 1585: Two Kapampangan noblemen revolt after a squabble concerning tax collection and Spanish judicial decisions. They kill the chief of Candaba, one of the nobles surrenders, and the other gets killed in a siege.

AD 1588: Conspiracy of the Lakans. By this time, Dionisio Capulong has become chief of Candaba.

Between July 1589 and June 1588: Dionisio Capulong is pardoned.

AD 1594: Dionisio Capulong leads Kapampangan soldiers to help Spanish expeditions in the Cordilleras.

Appendix

It’s unlikely that the Spanish changed Sinukuan’s name to Maria Sinukuan for evangelization, especially since some version of the Maria Sinukuan legend (ie the one recorded by Macario Naval in 1916) have Maria Sinukuan assisting people against the Spanish. Pikudta (fiction), Cuentung barberu (barbershop tales to pass the time while getting a haircut), and istoriang cutieru (coach/carriage tales to pass the time while traveling) are more than enough to explain how the legend got corrupted through centuries. Naval’s recorded version in fact takes place in Arayat, Pampanga, which was founded only in American times. No one would seriously consider the Aeneid to be a Roman corruption of Greek myth (despite its propaganda value to Augustus), for stories naturally evolve depending on the context of their telling. The myth of Sinukuan thus also naturally evolved as Pampanga became Christianized.

Luzon Tagalog also borrowed certain morphological traits from Kapampangan, like the d/r switch after vowels (contrast Marinduque “bunrok” with Luzon “bundok”),

Zorc, R. D. P. (1993). The prehistory and origin of the Tagalog people. Language—A doorway between human cultures: Tributes to Dr. Otto Chr. Dahl on his ninetieth birthday, 201-211.

Mallari, J. P. (2006). Linguistics and Ethnology against Archaeology: Early Austronesian Terms for Architectual Forms and Settlement Patterns at the Turn of the Neolithic Age of the Kapampangans of Central Luzon, Philippines. In Tenth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics.

Gaillard, J. C., Delfin Jr, F. G., Ramos, E. G., Paz, V. J., Siringan, F. P., Rodolfo, K. S., ... & Dizon, E. Z. (2003). Socio-economic impact of the c. 800-500 yr BP. eruption of Mt. Pinatubo (Philippines) Hypotheses from the archaeological and geographical records. Proceedings of the Society of Philippine Archaeologists, 2, 46-58.

Beyer, Henry Otley (1947). "Outline Review of Philippine Archaeology by Islands and Provinces". The Philippine Journal of Science. 77 (3–4): 205–374.

Melendres, R. G. (2014). The utilization of Candaba swamp from prehistoric to present time: Evidences from archaeology, history and ethnography. Bhatter Coll. J. Multidiscip. Stud, 4, 81-93.

Mallari, J. P. (2006). Linguistics and Ethnology against Archaeology: Early Austronesian Terms for Architectual Forms and Settlement Patterns at the Turn of the Neolithic Age of the Kapampangans of Central Luzon, Philippines. In Tenth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics.

Hernandez, Vito Paolo Cruz (2010). Human Occupation of Pampanga's Coastal Lowlands: Implications of the Effects of Post-Depositional Processes on Artefacts and Sediments from Lubao, Pampanga (Philippines)

Gaillard, J. C., Delfin Jr, F. G., Ramos, E. G., Paz, V. J., Siringan, F. P., Rodolfo, K. S., ... & Dizon, E. Z. (2003). Socio-economic impact of the c. 800-500 yr BP. eruption of Mt. Pinatubo (Philippines) Hypotheses from the archaeological and geographical records. Proceedings of the Society of Philippine Archaeologists, 2, 46-58.

Rodolfo, K. S., & Umbal, J. V. (2008). A prehistoric lahar-dammed lake and eruption of Mount Pinatubo described in a Philippine aborigine legend. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 176(3), 432-437.

Mallari, J. C. (2009). King Sinukwan Mythology and the Kapampangan Psyche. Coolabah, (3), 227-234.

Juan, G. B. (2005). Ma'l in Chinese Records-Mindoro or Bai?: An examination of a historical puzzle. Philippine Studies, 53(1), 119-138.

Crossley, J. N. (2018). Dionisio Capulong and the elite in early Spanish Manila (c. 1570–1620). Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 28(4), 697-715.

Joaquin, N. (1988). Culture and history: Occasional notes on the process of Philippine becoming. Solar Publishing Corporation.

Potet, J. P. G. (2017). Ancient beliefs and customs of the tagalogs. Lulu. com.

Potet, J. P. G. (2013). Arabic and Persian loanwords in Tagalog. Lulu. com.

Larkin, J. A. (1972). Pampangans. University of California Press.

Santiago, L. P. (1990). The Houses of Lakandula, Matanda and Soliman (1571-1898): Genealogy and Group Identity. Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society, 18(1), 39-73.