This piece is from a chapter explaining ideologies in A Gentle Introduction to Pillar of Liberty.

While it may be an easy temptation to try and consider absolutism as a singular tendency that finds expression in a myriad of forms, it is important to note that the historical roots of absolutism rest on a myriad number of places and conditions, each slowly resolving itself under a framework that is retrospectively similar from the perspective of modernity. Technological, cultural, religious, and historical contingencies play an important role in separating the kinds of absolutism from one another, to the point that absolutism itself may be regarded less as a coherent framework and more as a shorthand term usable for laymen.

As such, absolutism can be regarded as an ideal form consisting of these various criteria:

Centralization of law and justice under the office of the monarch (not in the specific person of the monarch but in the office of the Monarch itself, commonly referred to as the Crown) such that all arrangements pertaining to laws, contracts, and property are legitimized by affirmation of the Crown under its courts and enforcers rather than by custom or simple mutual agreement of the parties involved.

2. The existence of standing armies, as compared to the prior situation of relying on levies and local garrisons, such that the soldiers swear their allegiance not to their employers or localities, but to the monarch, irrespective of their location and status. Thus, the king can rely on a constant force of soldiers all over the kingdom to fight for his name and his law above all other considerations, making him less beholden to nobility and intermediaries.

3. The establishment of a singular bureaucracy, who is beholden primarily to the Crown and whose primary purpose is to maintain and establish a regularity to the operations of the centralized state in all corners of its territory. This would greatly weaken the primacy of peripheral authorities to properly administer their localities given the oversight and intervention of bureaucrats in their pertinent fields and affairs.

Depending on the technological level (speed and ease of communication and transportation, sophistication in technical and agricultural ability, capacities for numeracy and literacy) and the probity (ability to resist being influenced or bribery, impartiality in asserting power, adaptability towards local conditions) of bureaucrats in the polity, such a bureaucracy may provide net benefits to such a polity in the near to medium-term. By such a framework, it is possible to gauge the likelihood of any given state as achieving or leading to the formation of an absolutist state. Such developments may occur under different sets of circumstances, such that absolutism may be achieved in an organic and developmental fashion (meaning that these would come into being as an emergent property of regular, repeated interactions between subordinates within the state and the subjects of the state themselves) or be imposed upon the state through a clear and intentional manner (meaning that rulers would exert their power in such a way as to create and formalize these arrangements with

the acquiescence or submission of the rest of the polity). These distinct ways need not be mutually exclusive, and the historical development of absolutist states shows that both were often needed and worked in tandem in order to fully establish absolutism within their polities, with examples being the post-Hàn Chinese dynasties and early modern France.

Absolutism was a significant motivator in the disintegration of the medieval political consensus, at least in Europe, as it afforded greater political, economic, and military power for those who initiated and participated in it. For kings, absolutism provided greater wealth and prestige as theparamount leader of their realms. For the nobility, bureaucracy meant the ability to place themselves, their allies, or their loyalists in positions of power with the blessing and backing of the crown, as well as the ability to allow the king to place administrators that they then could bribe or corrupt, with little loss and plenty of gainst to accrue to themselves, to be further offset by the greater overall wealth produced and the increased ability to participate in government

within the center. For the military and bureaucracy, it meant an increase in their own size and strength, while also offsetting the chaotic and patchwork arrangements that left them either non-existent or bound to infirm local authorities. More importantly, for the peasantry and the burgeoning merchant classes, absolutism engendered an imposition of regularity for transactions, policies, and enforcement that enabled streamlined interactions by curbing the onerous tendencies of local authorities.

In an age where exploration and colonization became key objectives for growing nations, absolutism was essential in attaining the institutional constancy that would promote colonization efforts, mercantile trade, and resource extraction, while also maintaining cohesion and security within their own realms. This can be observed through the failure of decentralized polities to resist the greater strength of absolutist states, such as the tragic defeat of the Kingdom of Hungary in the Battle of Mohács at the hands of the Ottoman Empire, and the disintegrations of the Holy Roman Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth at the hands of Napoleonic

France and the tripartite agreement between Russia, Austria, and Prussia, respectively.

However, absolutism need not be a convergent phenomenon with colonialism, as the

aforementioned example of post-Suí China never resorted to the same persistent level and degree of colonial adventurism as its Western counterparts had exhibited. To buttress the legitimacy of the new absolutist state of affairs, different principles had emerged in order to justify it to the rest of the polity. In East Asia, this principle was known as the Mandate of Heaven, which attributed both the fortunes and misfortunes of the realm squarely at the feet of the rulers as the blessings of heaven, but also specifically allowed for a right of replacement by the discontented or the strong to remove the rulers and then establish their own dynasty. This legitimized the replacement of the ruling class by anyone who could militarily contest their rule, whether by an internal rebellion (such as the case of the replacement of the

Goryeo dynasty by the Joseon dynasty in Korea) or by an external imposition by an occupying force (such as the case of the Mongol establishment of the Yuán and the Manchu establisment of the Qīng in China). Of particular note here is that even when the ruling class is replaced under such a principle, there is no question that the centralized absolutist structure of the state is retained, with the absolute monarch and his ministers simply being replaced, and other such changes to be made as reforms of the extant system rather than a wholesale replacement. Practically speaking, the size and centralization of China was such that it was impossible for any claimant to ignore or consider replacing the extant bureaucracy and absolutist framework without such claimant itself meeting a viable challenge (the closest

example of any such radical change being the failed Tàipíng Rebellion). Barring specific instances when China was subdivided between multiple smaller states and statelets, such as the Warring States Period, the Mandate of Heaven implicitly extended to all of China, and that part of achieving this mandate was asserting rule over the whole of China, as the central realm of the earthly domain, and which spread to its neighboring nations with a similar framework, such as Korea and Vietnam.

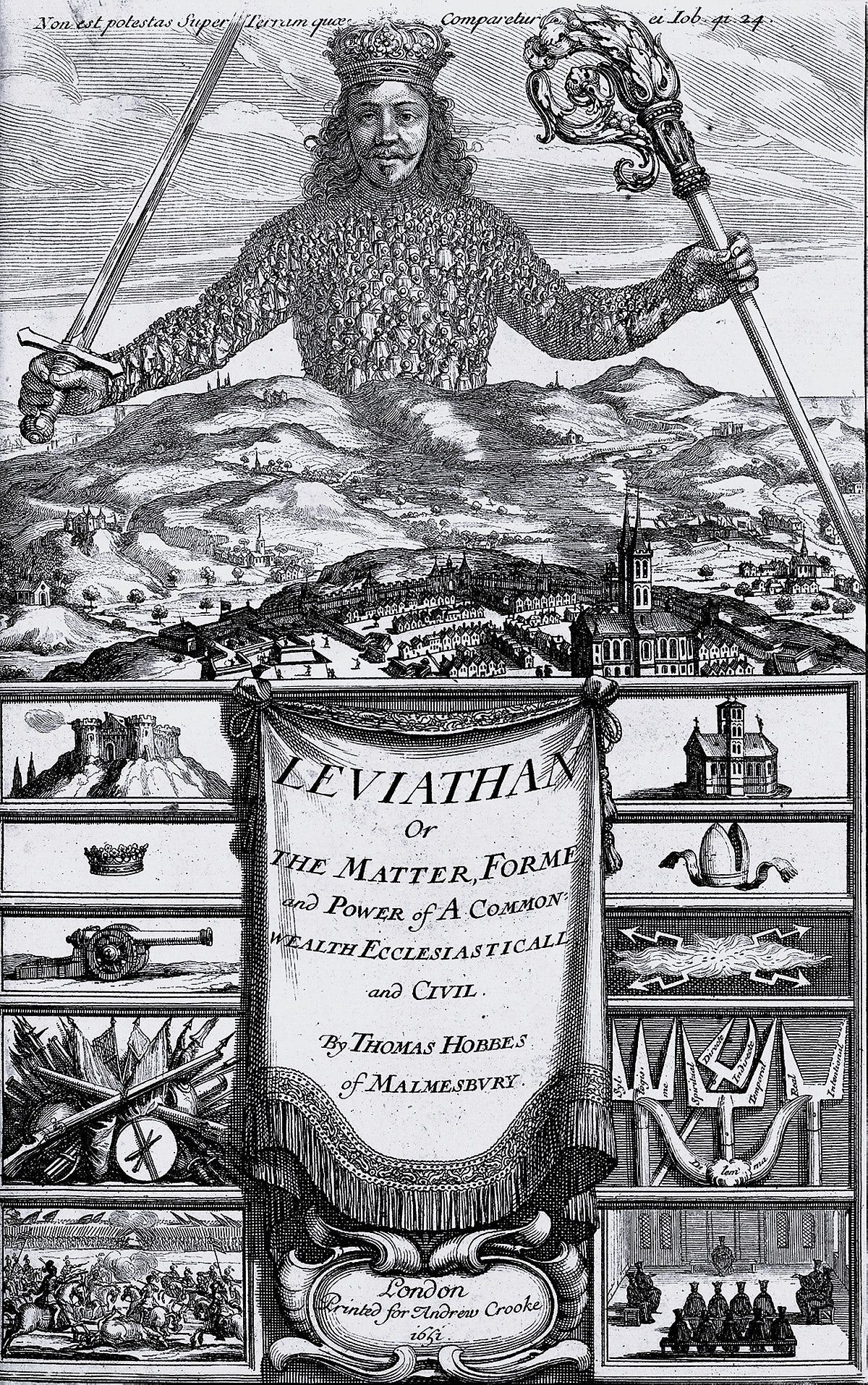

For Europe, this principle was known as the “divine right of kings”, where monarchs derive their power and sovereignty as instituted by God, and as such was unimpeachable by anyone else apart from Him or the different exigencies of life, such as illness or death. Of important note here was the subtle repudiation of any binding subjection and responsibilities that a king may have under the previous Medieval order and the excision of the Catholic Church and its previous position as first among equals in terms of precedence among monarchic rulers. Whereas before, the Pope may condemn individual rulers and act in God's stead in order to select new

rulers to replace them, the absolutist state made no such formal claim of order and effectively claimed God's approval for any prospective claimant who can establish and enforce such a claim over a given territory. Thus, in contrast with a feudal order that can trace a direct line of hierarchy from the lowliest peasant to their king and then to the Pope, absolutism in the West accelerated political differentiation between nations even while dismantling such within their own borders. Crucially, unlike the example of the East, the divine right of kings did not explicitly stipulate a right of replacement, whether by subjects or by stronger rivals. The legitimacy of aspirant monarchs, and implicitly the whole underlying absolutist system under their rule, was

thus as much established through the principle as it was through mutual arrangements, non-contestation, and custom from among the various monarchs of Europe.

Islam's arrangements with absolutism are somewhat similar yet also distinct

from the European example, primarily as a result of the historical development of Islamic beliefs regarding temporal and spiritual authority, and would not be a primary focus for this treatise given that it too has been largely supplanted by political modernity as derived from the Western example.

Meanwhile, the development of absolutist arrangements in the British Isles would take a slightly different direction, given the strength of the British Parliament as an institution that can and did oppose the monarch on occasion, providing safeguards of custom and tradition that placed Parliament in the effective position of exercising what would be the monarch's absolute power in the other nations of Europe. It would take little effort later on for the supremacy of Parliament to adapt to the notion of popular sovereignty in effect and implicitly even while retaining the forms and structures of monarchical rule. Later on, political modernity in the United

States would follow this basic framework, while integrating ideas from Europe, and eschew any monarchical or customary arrangements by forming a new republican government altogether, resting on both popular sovereignty and a written constitution, a model that would become the basis for similar arrangements elsewhere in the world.

For Europe overall, however, the cause of absolutism would be greatly strengthened by the divisions within Christianity as a result of the Protestant Rebellion, many of whose leaders explicitly repudiated the authority of the Pope as first among equals of the monarchs of Christendom and proclaimed equality among sovereigns. Monarchs who had felt ignored, repressed, or did not care as much for the status of Rome eagerly embraced such rebellion, and greatly contributed to the decline in the nominal temporal authority of the Church, as well as the aforementioned arrangements of custom and non-contestation in the aftermath.

All these would precipitate in the development of the ideals of modernity, where specific and formal institutions of authority were divested from divine order and reduced to institutions resting on tangential loyalty and force (whether legal or armed). It would not take long for corruption to reassert itself within absolutist systems, as even bureaucrats were not immune to court intrigueor the allure of illicit wealth and property. The increased need for direction and guidance from

the center also enabled a wide latitude of rent-seeking and corrupt behavior in order to skirt the restrictions of the law or to profit from it. Levies and taxes on trade and manufactured goods brought vast wealth that by necessity had to pass through local administrators first before being allowed to reach the center or be permitted for export, opening up opportunities for bribery, smuggling, counterfeiting, and other nefarious activities. The lack of speedy and effective communications meant that the center could not receive information and regulate the activities under its purview as efficiently as it could, nor could it plan for eventualities and contingencies properly. Even if it were possible, the conduct of such actions would have been left at the hands

of individuals who largely did not have the right set of knowledge and skills, as well as the mental acuity or moral fortitude, to be able to deliver on such potentiality.

The political phenomenon of modernity is attributed to have begun in the West primarily as a result of the inability and stagnation engendered by the smaller (compared to China, at least) kingdoms and polities of Europe and pivotal instances of economic downturn and the continued breakdown in religious unity and authority as a result of the Protestant Rebellion. In continental Europe, the crucial event of the French Revolution was precipitated by large-scale famine in 1788, with France's leadership occupied as it was with geopolitical rivalries with Great Britain and which led it to send sizeable sums of money to the nascent American Revolution, which prevented France from engaging in an effective response if its ruling class so desired.

The French Revolution would lead to the overthrow of the long-standing absolutist French monarchy and the establishment of a revolutionary republic that eschewed any notion of sovereignty as originating from God and instead invested it largely with the people of France. With sovereignty vested in the people, expressed through the act of voting, and exercised through the actions of the government, the absolutist order was thus reoriented towards upholding the abstract concepts of ‘liberty’, ‘rights’, and the ‘nation’, and away from the concrete and reciprocal obligations imposed and maintained by the Church, actual kings, lords, lieges, and subjects in both medieval and absolutist systems.

The shift here is pivotal because no institution can claim any relative or absolute jurisdiction over the proper nature and end of these abstract and irrevocably foundational concepts. As free and equal citizens, the deliberations brought about by the democratic process are provisional at best and can be changed simply in an electoral cycle by those elected and who have a different view regarding these concepts, or be constrained by the enforced reasoning of the courts1.

Rather than an actual sovereign imposing his will on his subjects, the plural sovereign of the people arrives at a majority (or plurality) decision which is then enforced on everyone else as binding, as everyone is bound necessarily by what would be termed as a ‘social contract’ in order to achieve the protection and enlightenment of the law rather than simply private or factional avarice, with the proviso that the majority is fluid with respect to the issues at hand and may bind oppositely for those in the majority beforehand but in the minority afterward. It is also important to note here that all three marks of absolutism are still retained and applied, even if the structure for arriving at decisions and securing legitimacy have been transformed.

Absolutism under a so-called democratic society provides an alternative sense of political and social stability, given that decisions are not perceived to be arbitrarily coming from an external figure with no accountability to his subjects. Decisions under a democracy are achieved and arrived at by means of an electoral process and through accountable (replaceable or impeachable) representation. Corrections and reprimands are supposed to be easily applicable given the lack of legal distinctions among citizens, such that the law does not provide uneven protection, and are supposed to be regularly possible through measures such as term limits or popular referenda, enabling the determination of a popular majority to decide the legitimacy of certain proposals. The public has, in a sense, a real stake in the direction and progress of their society since they participate in its sovereignty as partial sovereigns of their own, may object or refuse to assent and cooperate with most mandates of the law (excepting certain circumstances, such as for criminal law or for emergency situations, but even such exemptions are vulnerable to democratic reinterpretation), and are notionally protected by the law from reprisal and violence in the case of opposition or dissent.

However, this does not obviate, and even exacerbates the problems of an absolutist state, given that the effective and practical deliberation and execution of sovereign decisions still does not rest with the people as a whole, but through the representatives, administrators, and judges that have arisen from the democratic process. Under a democracy, the reach of the state may even expand, as citizens may be enjoined or convinced to demand and support laws regarding certain subjects that an individual, monarchical sovereign may not even deign to consider, and that the public may not object to if done under the idea that such decisions had been arrived at through the democratic process. Consider the example of any important political issue, such as abortion or gay ‘marriage’, and examine what and how the public reaction would be if an individual monarch had unilaterally made a firm decision to uphold or to outlaw such. The reaction thereof, would be something completely different than under a democratic framework, and may even become violent if the issue were sufficiently grave, such as for economic or ethnic/cultural issues. The democrat somewhat minimizes such tensions, if only up to a point, but also engenders a certain moral corruption, vitiating the righteous moral disgust and

apprehension of the citizenry on issues of fundamental importance as long as it can be properly mediated through the democratic channels and it is conceptually justified in accordance with the abstract principles underlying the ideological framework of democracy.

Furthermore, the human frailties of individual citizens within the government or as voters still very much remain, and bribery and corruption remain viable even as the framework in which they are considered to be reprehensible has become changed. As a result of strict limits on holding office and the exercise of influence, democracies foster short time preferences in the decision-making processes of the body politic, such that projects and policies are at perennial risk of alteration or cancellation should the electoral process resolve for a change in government instead of continuity. For actual and useful projects, this could lead to decreases in quality in order to achieve completion before possible change, or scuttle any viable long-term planning

and projects if those politically committed and responsible for such become incapable of maintaining a sense of regularity and constancy. In another sense, democratic absolutism engenders usufruct utilization, wherein officeholders and other officials are behooved to extract and make use of as much resources, leverage, and influence as they could for their own benefit before they themselves are subject to democratic or legal removal, while also encouraging the proliferation of projects and plans that would ideally mature during a specified term or length of time that would be in accordance with political goals, irrespective of their actual validity and

usefulness to the public, and may only be an attempt to retain the confidence of the public sovereign.

Next Section: Absolutism, Managerialism, and Revolution (Manipulating procedural outcomes).

Distinctions on emphasis may also help in explaining certain differences between English common law and French-derived civil law, specifically the latter's objections to case law and precedent. In a society where popular sovereignty determines the form and content of the law, precedent can only render confusion and allow judges to impose the law apart from what the elected state (the direct instrument of popular sovereignty) may prescribe. In contrast, in a society where popular sovereignty is seen to be necessarily mediated through intermediary institutions and figures like Parliament/Congress, courts and judges, and the actual Constitution, what is binding must also necessarily refer to and originate from these, so as to oppose popular tendencies towards mob rule and revolutionary violence, of which contemplation and rational agreement may defuse given discipline and proper reasoning